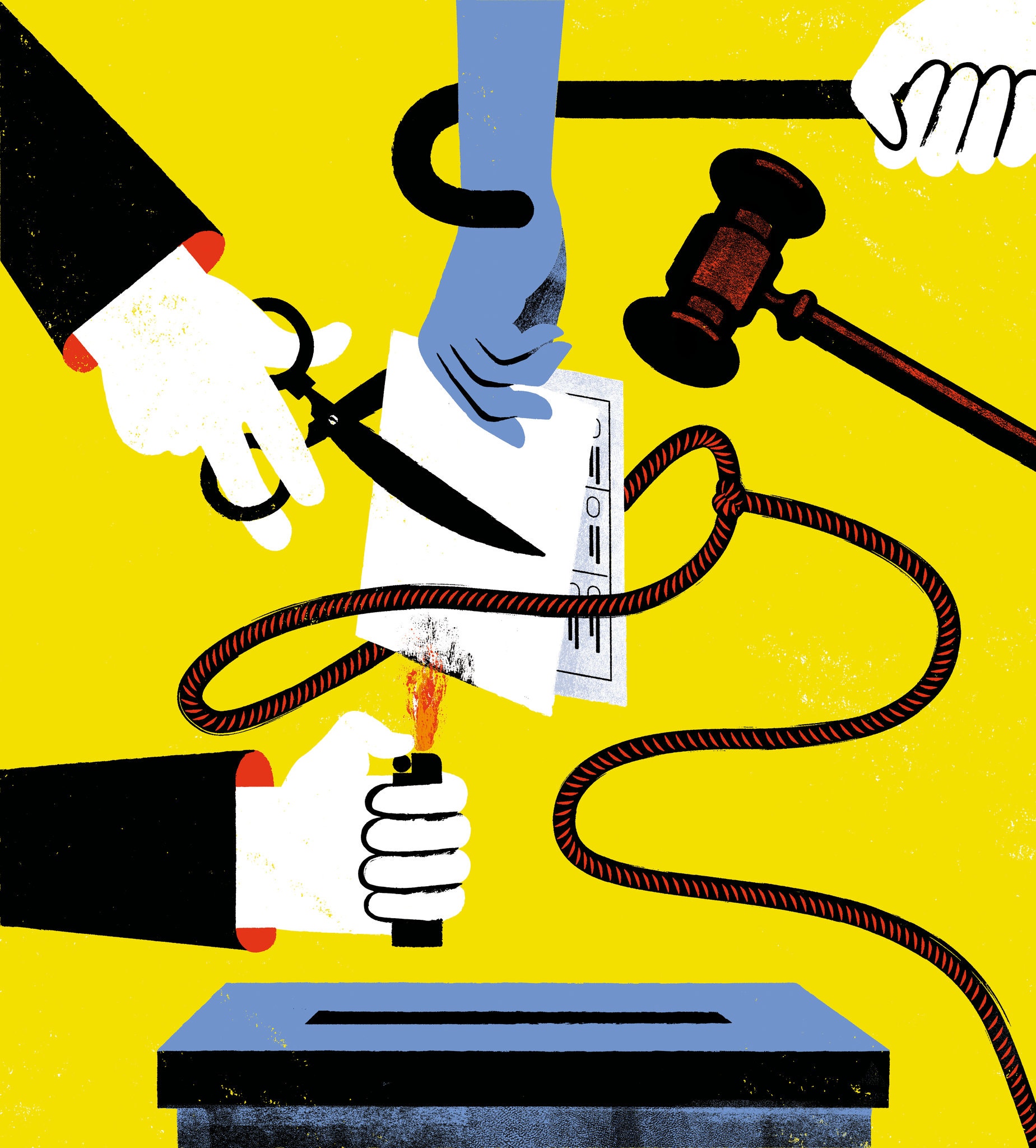

According to their “Voting Laws Roundup” as of February, The Brennan Center for Justice makes this observation concerning potential changes to voting laws across the country — “In a backlash to historic voter turnout in the 2020 general election, and grounded in a rash of baseless and racist allegations of voter fraud and election irregularities, legislators have introduced well over four times the number of bills to restrict voting access as compared to roughly this time last year.”

Why not? Our country has an ugly history of taking away the voice and vote of persons who disagree with those holding power. This attitude disproportionately affects persons of color. We continue to have large numbers of white supremacists in our midst. Many of them are elected officials, trying to take us back to the time of The Naturalization Act of 1790, which limited U.S. citizenship to whites only. While various naturalization acts and laws followed the original one, it was 1965 before both men and women of color could vote. But legal authority often doesn’t translate into practical authority.

The landslide victory of Joe Biden and Kamala Harris was a wake-up call for white supremacists. It’s abundantly clear that allowing all Americans to vote will make it more difficult for the U.S. to go back to a time when white privilege was protected by law. You wonder why so many otherwise intelligent politicians continue to lie about our last election’s integrity? To answer this question, you can look no further than lawmakers’ actions in our own state.

You and I struggle to deal with a deadly pandemic, recovery from poisoned water, high unemployment, food insecurity, and more. Meanwhile, many of our state legislators are spending their time finding creative ways to take away the vote of persons that don’t benefit from privilege.

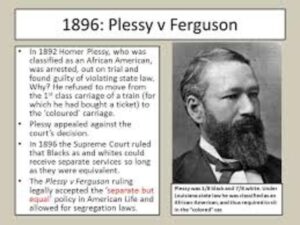

In her book, Be the Bridge, Latasha Morrison writes about a mixed-race man, one-eighth Black, named Homer Plessy. Mr. Plessy was publicly humiliated by a railroad employee after buying a first-class ticket in the Whites-only section of a passenger train in New Orleans. Apparently, aware of Mr. Plessy’s lineage, the conductor instructed him to give up his seat. When he refused, he was arrested. 1

Though Mr. Plessy’s skin tone was light enough that he appeared to be White, the judge cited the one-drop rule: anyone with at least one drop of non-White blood was automatically classified as “colored” under the law. Even though Mr. Plessy argued that the judgment violated the Fourteenth Amendment, which guaranteed equal protection (and treatment) under the law, the Supreme Court upheld the lower court’s decision. In 1896, Louisiana’s separate-car law was upheld, allowing segregation under the “separate but equal” doctrine.

Latasha reminds us that “Colorism in the United States was long promoted by the White community as a way to divide and conquer African Americans,” citing a few notorious examples.

One example, is a theologian named Samuel Stanhope Smith (President of the College of New Jersey, now known as Princeton University) argued that having lighter skin, straighter hair, and slimmer noses and lips was representative of “civilized society.”

One example, is a theologian named Samuel Stanhope Smith (President of the College of New Jersey, now known as Princeton University) argued that having lighter skin, straighter hair, and slimmer noses and lips was representative of “civilized society.”

Another prominent individual that promoted colorism was a sociologist named Edward Byron Reuter. He published The Superiority of the Mulatto, where he argued that significant achievements in literature, medicine, and business, within the Black community, were accomplished by biracial, light-skinned people. Latasha’s obvious conclusion, “What is colorism if not a form of white supremacy?”

In Be the Bridge, Latasha reminds us that “Confession requires awareness of our sin, acknowledgment of it, and the desire to move past the shame and guilt.” But Latasha also points out that, “Confession also requires great humility and deep vulnerability.”

We can add to Latasha’s observations constructively. For example, confession, particularly confession that we did harm to another person, requires great courage. Perhaps more courageous is to admit that privilege gives us an advantage. It’s intimidating to wonder whether, without privilege, we wouldn’t have what we want to believe we earned.

These observations are essential when evaluating the character of those carrying weapons to intimidate the courageous persons bringing attention to Black Lives Matter. In this case, I see cowardice, which is ironic given the macho stance taken by armed white supremacists pictured as dressed for conflict with unarmed civilians.

Confess your sins to each other and pray for each other so that you may be healed.

James 5:16

The writer of the letter called James offers this advice, “Confess your sins to each other and pray for each other so that you may be healed” (James 5:16). Healing from generations of discrimination against persons of color is one of the primary goals of our series, Bridges. But for healing to be possible, we must name our sickness. This week, our collective sin that comes into focus is colorism. That is, our tendency to equate physical attributes to predictable outcomes resulting from centuries of inherited bias reinforced by systems, laws, and culture.

Latasha notes that “One of the major fears about confession is wondering what others will think of us.” I suspect this is true for most of us. God already knows everything that we’ve ever thought or done and loves us anyway. We confess so we can get well and live abundantly.

We have a new button on the homepage of our website – Click here to watch. This button takes you to a viewer to allow you to join live or watch later in the week. We’re also live on Facebook and our newly launched YouTube channel. You can find these links along with more information about us on our website at FlintAsbury.org.

A reminder that we publish this newsletter that we call the Circuit Rider each week. You can request this publication by email. Send a request to info@FlintAsbury.org or let us know when you send a message through our website. We post an archive of past editions on our website under the tab, Connect – choose Newsletters.

Pastor Tommy

1 Most of the content for our series comes from Latasha Morrison, Be the Bridge: Pursuing God’s Heart for Racial Reconciliation. Yates & Yates and Penguin Random House, 2019.